What Australia's gas-led recovery will mean for the

country's carbon emissions

By national science,

technology and environment reporter Michael Slezak

Posted 24th

Sept 2020 ABC News

An Australia Institute report estimated hundreds of millions of tonnes of carbon would be emitted if all of Australia's potential gas projects went ahead.(ABC Southern Queensland: Nathan Morris)

Australia's economic recovery from COVID-19 will be largely rebuilt on

fossil fuels, according to the Government. Specifically, on gas.

New basins will be opened up. New pipelines will be laid. New

gas-burning power stations will be built.

What will all this mean for climate change and Australia's commitment to

cut emissions?

Much has been said about the new gas hubs, power stations and pipelines.

But emissions from those will be chump change compared to the emissions

that will likely result from the opening up of even a single large gas basin.

The Government is talking about developing five new basins that it will

help fund.

Such a move is a proverbial red rag to conservationists who are fighting to stop

global warming at 2 degrees Celsius and whose mantra for years has been,

"Keep it in the ground".

Take the most advanced of these basins, already backed by the

Government: the Beetaloo sub basin in the Northern Territory.

A clearing in the

Beetaloo basin, with a small well in the centre, is part of gas expLoration in

the region.(ABC News: Jane Bardon)

If developed, government estimates show it could result in as much as 117 million tonnes of

CO2 being added to our emissions each year — almost a

quarter of our current total yearly emissions.

Adding

that to our emissions tally will make meeting Paris targets much harder — and it means we'll

have to find cuts in other areas, which the Government doesn't yet have a plan

for.

Estimates have suggested there's enough gas in the Beetaloo basin

to satisfy Australia's demand for 200 years.

But if we need our emissions to hit net zero in about 30 years, it's

unlikely the demand for gas will last anywhere near that long.

Some big fossil-fuel companies have acknowledged that. BP's latest

modelling suggests there will only be a small increase in the demand for gas if

the world does nothing to combat climate change.

Dozens of potential gas projects

The Government has listed dozens of new gas projects that have been proposed

by industry around Australia.

A report by The Australia Institute, commissioned by the

Australian Conservation Foundation, added up how much greenhouse gas would be

released into the atmosphere if these projects all progressed to their full

potential.

The figure is not realistic since they wouldn't all progress, and of

those that do, not all their gas would be extracted.

But it's indicative of how carbon intensive a gas-led economy could be.

Gas-fired path to

COVID recovery?

Combined with the gas from the Beetaloo

basin, the progressive think tank estimated the potential projects would

result in an average of 332 million tonnes of CO2 being emitted

each year.

That's

about two thirds of our current total emissions.

It's a carbon bubble that would be hard to make up for in other sectors.

The figure combines estimates of the CO2 emitted when the gas is burned,

as well as fugitive emissions of methane — essentially, gas leaks.

But there are also concerns even after gas wells are closed, they might continue to leak

methane into the atmosphere, making future action to stop emissions difficult.

UN report singles out Australia

The dilemma posed by opening up new fossil-fuel reserves has been

analysed by the

United Nations in what's called the

Production Gap Report.

It

notes specifically governments' support of the production of fossil fuels,

including gas, "undercuts efforts, sometimes by these same governments,

to reduce emissions".

Overall,

the report found around the world, countries are planning to produce 50 per

cent more fossil fuels in 2030 than would be needed to limit warming to 2C and

120 per cent more than is consistent with 1.5 degrees.

The planned production

of coal, oil and gas is far greater than what is required to limit climate

change.(Supplied)

Australia

was one of a handful of countries singled out in the report, with the Federal

Government's support of gas and other fossil fuels sharply criticised.

Australia's

proposed fossil-fuel projects represent "one of the world's largest

fossil-fuel expansions", the report said.

"The

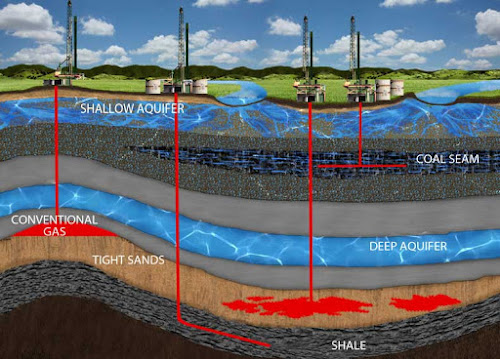

rise of hydraulic fracking has also opened the door to discussions on tapping

into the country's vast resources of unconventional gas."

The

report notes that while global coal production needs to drop by about two

thirds by 2030, gas production needs to drop significantly too — by about 20

per cent by 2030 — in order to keep warming at 1.5C.

Under the rules of the Paris agreement, we don't need to worry about the

emissions from much of our coal and gas because it's exported, and

therefore counted in other country's emissions targets.

According

to the UN's report though, the whole world is ramping up production of fossil

fuels, so the question of who will take responsibility for that carbon remains.

Gas vs coal

Federal Energy and Emissions Reduction Minister Angus Taylor has also

argued gas produces lower emissions than coal, and using gas instead of coal

will help lower emissions.

"The success of our LNG exports means that we can help lower

global emissions below what they would otherwise have been by up to 27 per cent

of Australia's annual emissions," Mr Taylor said.

The

UN's Production Gap Report dealt with this argument head on, noting increasing

the supply of gas would drive its uptake.

Gas-led recovery

without the $6b price tag

It

concluded: "The continued rapid expansion of gas supplies and systems

risks locking in a much higher gas trajectory than is consistent with a 1.5

degree Celsius or 2 degree Celsius future."

"Barring

dramatic, unexpected advances in carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology,

these declines mean that most of the world's proven fossil-fuel reserves must

be left unburned," the report said.

Making the unexpected happen is something the Government is betting on.

As part of its Technology Investment Roadmap, it's investing in CCS,

which has the potential to bury some of the emissions from these projects

underground.

The world's largest attempt at this is taking place at Chevron's Gorgon

gas project in Western Australia.

The

project planned to offset only 40 per cent of its emissions using CCS —

and it's been plagued with problems and delays, and didn't

capture any carbon for the first three years of its operation.

And,

since the world including Australia, has committed to stopping global warming,

it's hard to see exactly where our domestic gas push is leading.